Are psychological interventions effective in preventing relapse and recurrence in depression?

The World Health Organization estimates that approximately 280 million people in the world suffer from depression, the second top leading cause of years lived with disability globally (Global Burden Disease, 2019).

Not only is depression common, but up to 54% of patients who have experienced a depressive episode are likely to relapse (Bockting et al., 2015). Relapse is usually defined as the re-emergence of the initial episode of depression after some initial improvement, whereas recurrence is the onset of a new episode of depression after recovery (Moriarty et al., 2021). Previous studies have explored pharmacological (Cipriani et al., 2018) and non-pharmacological strategies (Buckman et al., 2018) to prevent both relapse and recurrence of depression.

It has been recommended that psychological interventions should be delivered more widely across the globe, trying to identify the people who may benefit the most from these interventions (Patel et al., 2023). However, the meta-analyses conducted so far have used aggregate data, which do not allow the stratification of treatment recommendations according to individual characteristics.

These limitations can be overcome – at least in part – with a methodological approach called individual participant data meta-analysis (IPDMA). Used by Breedvelt and colleagues (2024), IPDMA collects individual data from each participant across the studies included in the systematic review, thus enabling the stratification of patient subgroups and facilitating a more accurate analysis of outcomes (Tudur Smith et al., 2016).

Not only is depression common worldwide, but approximately 50% of patients who experience a depressive episode are likely to relapse, making relapse prevention an important area of research.

Methods

The authors systematically searched (until January 2021) for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published in four different electronic databases to assess the efficacy of psychological interventions in preventing depression relapse and recurrence, comparing Psychodynamic Psychotherapy, Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy, Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy, and Continuation Cognitive Therapy against non-psychological interventions and treatment-as-usual (TAU).

For the statistical analysis, a pairwise meta-analysis model based on IPD was adopted. Hazard ratio (HR) was chosen as the statistical measure to summarise time-to-event data. Due to the expected between-studies heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used, and heterogeneity was assessed with I2 statistic. A list of predefined predictors and moderators from previous studies was used for multivariate model analyses (Bockting et al., 2015; Buckman et al., 2018). Subgroup analyses were performed to compare the efficacy of different psychological interventions.

Results

This IPDMA included 14 studies involving 1,720 patients with major depression. Participants were predominantly female (73%) with an average age of 45.1 years and history of recurrent depression (average of 4.8 episodes, with 75% experiencing ≥3 episodes).

Unfortunately, information about important clinical and demographic characteristics was only available for the minority of participants: for instance, ethnicity (29%), employment status (56%), comorbid psychiatric condition (41%) or other medical conditions (23%), psychological sessions completed (49%), and previous psychological intervention (55%) or medication (23%).

The IPDMA showed that:

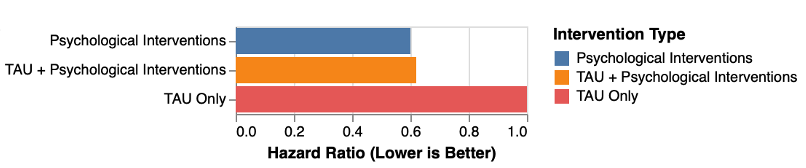

- Psychological interventions (as a group) outperformed control conditions in delaying the time to relapse accounting for a small heterogeneity (HR = 0.60, 95% CI [0.48 to 0.74], I2 = 14.9%) (please refer to the graphic below).

- Adding psychological interventions to TAU also reduced the risk of relapse when compared with TAU (HR = 0.62, 95% CI [0.47 to 0.82], I2 = 28.3%) (please refer to the graphic below).

Comparison between different active strategies in reducing the likelihood of relapse/recurrence of depression (Graphic created with RStudio by Rosario Aronica). View full size image

- Subgroup analyses found no difference in the efficacy of different psychological intervention types to prevent depression relapse/recurrence, both when considered as monotherapy and add-on treatment.

- The predictor analysis found that having more than two previous depressive episodes (HR = 1.03, 95% CI [1.00 to 1.06]) and residual depressive symptoms at baseline (HR = 1.08, 95% CI [1.04 to 1.13]) can influence the risk of relapse in the control group.

- Moderator analyses revealed that participants with three or more previous depressive episodes benefited more from psychological interventions when compared to those with two or fewer episodes (HR = 0.55, 95% CI [0.37 to 0.79])

- Moderator analyses also showed that psychological interventions were not more effective in reducing relapse for those with two episodes or fewer when compared to TAU (two episodes, HR = 0.85, 95% CI [0.37 to 1.92]; one episode, HR = 1.48, 95% CI [0.40 to 5.53]).

This research highlights the potential superior efficacy of psychological interventions in preventing depressive relapse compared to control conditions, especially for patients who have experienced multiple previous depressive episodes.

Conclusions

The findings from this IPDMA suggest that psychological interventions are efficacious in reducing depression relapse/recurrence risk, both as monotherapy and as add-on treatment.

These analyses identified two potential predictors of the expected outcome:

- Residual symptoms of depression at baseline, and

- Having experienced more than two episodes of depression.

Despite the encouraging results, replication studies are warranted and caution is needed before these findings can be translated into clinical practice. If there are enough studies and available data, it would also be important to carry IPD network meta-analyses, to shed light on the specific effects of individual psychological treatments and rank them based on their efficacy and tolerability profile.

Despite the encouraging results from Breedvelt et al. (2024), caution is needed before translating them into a clinical framework, and further research is warranted.

Strengths and limitations

This study was carried out by a world-class team of researchers and clinicians with expertise in depressive disorders and evidence synthesis. The authors should be complimented for such an important effort: collecting and harmonising individual data from trials is always a gigantic and complicated task.

The major strength of this study lies in the inclusion of IPD within the meta-analysis framework. This approach enables gathering demographic and clinical data from participants across all the included studies, and also allows the identification of potential predictors and moderators of the outcomes (Huang et al., 2016). Predictors and moderators explore the between-individuals variance of treatment response, but they are quite different. Predictors are used to determine which patient may benefit the most from a given treatment, while moderators reveal which characteristics render a particular treatment more effective than another for a given patient (Vousoura et al., 2021).

Authors adhered to the PRISMA-IPD reporting standards guidelines (Stewart et al., 2015), and pre-registered the study protocol on PROSPERO.

As all methodological approaches, IPD meta-analyses have some limitations. One of these is the difficulty to retrieve IPD from previous trials, as experienced by Breedvelt and colleagues who managed to get access only to 18 out of the 28 trials identified. Additionally, the incompleteness of the dataset, particularly in terms of demographic and clinical information, represents a further weakness, which limits the external validity of the findings.

As reported in the IPDMA protocol, the authors used some strict selection criteria for their analysis: time to follow-up restricted to 12 months, the exclusion of studies not measuring time to relapse, and the exclusion of naturalistic studies on the long-term effect of active interventions. This approach, while intended to mitigate bias and increase internal validity, may affect the generalisability of findings, potentially limiting the use of these data to broader clinical contexts.

Moreover, although a risk-of-bias assessment tool was employed to evaluate the quality of the included studies (Furlan et al., 2015), the most recent Cochrane guidelines encourage the adoption of the Risk-of-Bias assessment tool 2 (RoB 2) (Sterne et al., 2019). This updated framework offers a more granular assessment per outcome, rather than per study, allowing a better understanding of certainty of evidence.

Individual participant data (IPD) meta-analyses are limited by the difficulty of retrieving IPD from existing trials, and by the amount of missing information in the datasets available.

Implications for practice

From a clinical perspective, this study answers many questions and suggests new ones:

- Is (psychological) treatment indicated after a depressive episode? If so, which approach should be adopted and for how long?

- Are different psychological approaches equally effective across the patient populations?

- Can we tailor interventions to subgroups of patients who are more likely to benefit from psychological treatments?

The findings from Breedvelt et al. (2024) on psychological interventions offers promising insights for clinical application, suggesting that psychotherapies are effective in preventing depressive relapse (and recurrence) for a specific subgroup of patients. Should future studies with broader and more diverse patient cohorts validate these findings, the implications will be significant, particularly for clinicians dealing with patients who prefer not to take pharmacological interventions.

This study can provide helpful strategies for clinical practice: it identifies predictors of relapse and recurrence, offering clinicians potential clinical biomarkers for patient stratification. Such personalised approaches support the shift from a one-size-fits-all approach towards more personalised care: the right treatment for the right patient at the right time. Accounting for specific patient’s needs, preferences, and risks, this model underscores the importance of a person-centred approach via shared decision making.

The study by Breedvelt and colleagues is an important contribution in the field of precision mental health, where researchers and clinicians aim to target treatment to individual patients improving outcomes and reducing the disability and global burden of depression.

Statement of interests

Andrea Cipriani and Rosario Aronica work in the Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford where one of the authors (Professor Willem Kuyken) of this manuscript also works; however, this blog was drafted independently by the two authors.

Primary paper

Breedvelt, J. J., Karyotaki, E., Warren, F. C., Brouwer, M. E., Jermann, F., Hollandare, F., … & Bockting, C. L. (2024). An individual participant data meta-analysis of psychological interventions for preventing depression relapse. Nature Mental Health, 1-10.

Other references

Bockting, C. L., Hollon, S. D., Jarrett, R. B., Kuyken, W., & Dobson, K. (2015). A lifetime approach to major depressive disorder: The contributions of psychological interventions in preventing relapse and recurrence. Clinical Psychology Review, 41, 16-26.

Buckman, J. E. J., Underwood, A., Clarke, K., Saunders, R., Hollon, S. D., Fearon, P., & Pilling, S. (2018). Risk factors for relapse and recurrence of depression in adults and how they operate: A four-phase systematic review and meta-synthesis. Clinical Psychology Review, 64, 13-38.

Cipriani, A., Furukawa, T. A., Salanti, G., Chaimani, A., Atkinson, L. Z., Ogawa, Y., … & Geddes, J. R. (2018). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet, 391(10128), 1357-1366.

Furlan, A. D., Malmivaara, A., Chou, R., Maher, C. G., Deyo, R. A., Schoene, M., … & Van Tulder, M. W. (2015). 2015 updated method guideline for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back and Neck Group. Spine, 40(21), 1660-1673.

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. (2022). Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry.

Huang, Y., Tang, J., Tam, W. W., Mao, C., Yuan, J., Di, M., … & Yang, Z. (2016). Comparing the overall result and interaction in aggregate data meta-analysis and individual patient data meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore), 95(14), e3312.

Moriarty, A. S., Meader, N., Snell, K. I. E., Riley, R. D., Paton, L. W., Dawson, S., … & McMillan, D. (2022). Predicting relapse or recurrence of depression: Systematic review of prognostic models. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 221(2), 448-458.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., … & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372.

Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Kohrt, B., Kieling, C., Sunkel, C., … & Herrman, H. (2023). Transforming mental health systems globally: Principles and policy recommendations. The Lancet, 402(10402), 656-666.

Shinohara, K., Efthimiou, O., Ostinelli, E. G., Tomlinson, A., Geddes, J. R., Nierenberg, A. A., … & Cipriani, A. (2019). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antidepressants in the long-term treatment of major depression: Protocol for a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 9(5), e027574.

Simmonds, M. C., Tierney, J., Bowden, J., & Higgins, J. P. T. (2011). Meta-analysis of time-to-event data: A comparison of two-stage methods. Research Synthesis Methods, 2, 139-149.

Sterne, J. A., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., Blencowe, N. S., Boutron, I., … & Higgins, J. P. (2019). RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 366.

Stewart, L. A., Clarke, M., Rovers, M., Riley, R. D., Simmonds, M., Stewart, G., & Tierney, J. F. (2015). Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD statement. JAMA, 313(16), 1657-1665.

Tudur Smith, C., Marcucci, M., Nolan, S. J., Iorio, A., Sudell, M., Riley, R., … & Williamson, P. R. (2016). Individual participant data meta-analyses compared with meta-analyses based on aggregate data. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9(9), MR000007.

Vousoura, E., Gergov, V., Tulbure, B. T., Camilleri, N., Saliba, A., Garcia-Lopez, L., … & Poulsen, S. (2021). Predictors and moderators of outcome of psychotherapeutic interventions for mental disorders in adolescents and young adults: protocol for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10, 1-14.

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Depression. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

Zhou, X., Teng, T., Zhang, Y., Del Giovane, C., Furukawa, T. A., Weisz, J. R., … & Xie, P. (2020). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antidepressants, psychotherapies, and their combination for acute treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(7), 581-601.